Jacqueline Crooks on her novel, Fire Rush: "It's about channelling the rage from my childhood"

The west London-raised author recalls the Southall uprisings of 1979, champions the joyful revolution of dub reggae music, and finds catharsis in the heroine’s journey of her debut novel, Fire Rush

In my last post, I wrote about how music helped me to feel reconnected to Southall, west London, this summer, after a lifetime of drifting from the town, where my grandparents landed when they emigrated from Punjab in the 1960s. I recalled attending a dub reggae night at a football club in nearby Hayes back in June. The sense of communion and shudder of bass combined to produce a potent, nostalgic healing, plugging me back into a long tradition of sound system culture among the grey and green Heathrow suburbs that raised me.

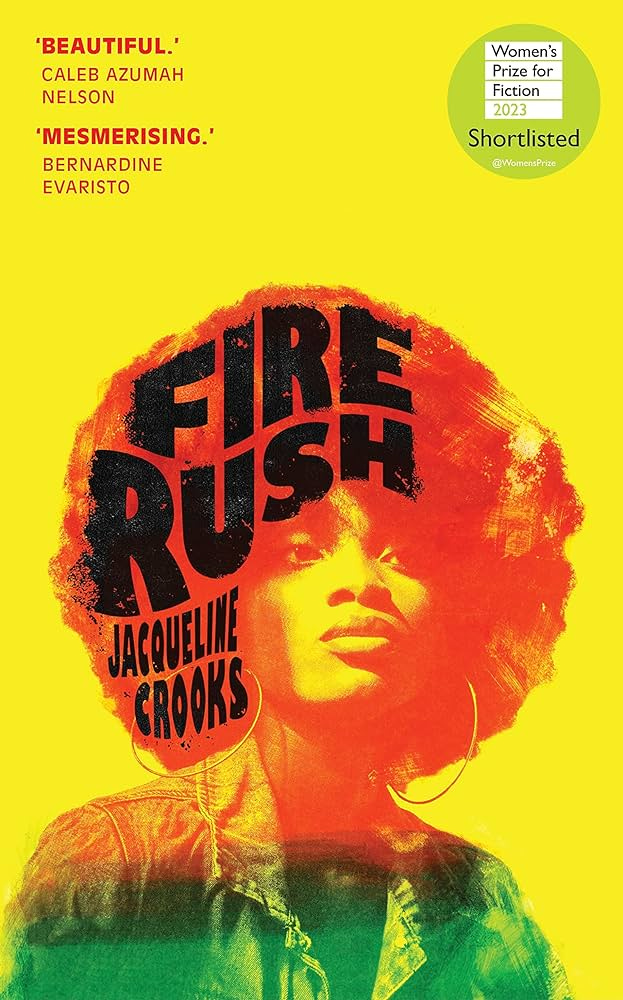

The morning after, feeling inspired, I scanned the internet for a book to read about dub music in the UK. My ribcage was still vibrating and ears were ringing from the night before when a new novel called Fire Rush by Jacqueline Crooks caught my attention.

A magical, immersive story that follows a protagonist called Yamaye, a young woman whose adventures are based on Crooks’s own life experiences, Fire Rush is written with a rhythmic, lyrical blend of English and Jamaican patois. Its first act is set in Southall as Margaret Thatcher is poised for political power, at the end of the 1970s, with racial tensions rising across Britain.

As a teenager, Crooks was immersed in a hidden subculture of blues parties that would take place in cellars and underground crypts, affordable spaces for young Black-Caribbeans in the area to protect their dances from police raids and prejudicial door policies. Local reggae bands like Misty In Roots and venues like Southall Community Centre and The Tudor Rose would become the building blocks of a proud musical ecosystem which lives on today through the local Punjabi community’s penchant for blasting dub from their souped-up classic cars.

Overwhelmed by the darkness of her youthful angst, Yamaye feels trapped by her broken family home. But she finds solace and community at The Crypt, a makeshift club beneath a church, whose doors she escapes into at night to dance her troubles away. She falls in love with a charming sculptor called Moose, but it isn’t long before tragic injustice cuts their union short, leaving her unanchored.

After the anti-fascist uprisings that gripped Southall in 1979 — during an era of protests in multicultural communities across the UK — Yamaye run away to Bristol, in the west of England. She is drawn into a criminal gang under the manipulation of Monassa, who is, with magical realist flair, evoked by Crooks as part-man, part-duppy, a toxic projection of Yamaye’s fears and vulnerabilities.

In the book’s third and final act, Yamaye travels to Jamaica seeking peace and light, shedding the skin of adolescence and embracing womanhood.

The book took 16 years to write. The hardback is out now, published by Jonathan Cape (Penguin); the paperback is forthcoming in early-2024. It’s been shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction and the Waterstones Debut Fiction Prize. Crooks was listed as one of the Observer’s best 10 new novelists for 2023.

I caught up with her about growing up in 1970s west London, understanding dub reggae as music for joy and revolution, and how she found catharsis by channelling her childhood rage into Yamaye’s epic heroine’s journey.

Ciaran Thapar: Hi Jacqueline. Why did you write Fire Rush now?

Jacqueline Crooks: I think it was less about me writing it now than me being ready for it now. I started writing it 16 years ago, and I started sending it out as a novel 10, 12 years ago, and no one was interested. I did have an agent back in 2005, but they asked me to write less patois. I thought, nope! So I wrote more patois. And they dropped me. Well, it wasn’t just because of the patois; that was one reason. We realised that she wasn’t getting the cultural significance. The book wasn’t quite ready. I thought to myself: I’ve got to do it my own way. I had a vision of the language and how I wanted to write it, so I wasn’t going to publish it until I’d realised that vision. I got a new agent in 2018. It was about what the world was ready for. Maybe it was George Floyd — the book was bought after his death.

So during the pandemic?

It was strange, because it was lockdown and I was told I had to shield, due to health problems, so my lockdown was completely isolating. I had to be on extreme lockdown. So there I was, writing about Yamaye, who experiences being locked down in a safe house, and there I was in the same situation whilst I was doing the edits for the publisher. I spent a year editing and finalising it. I had spent so long getting myself an agent and suddenly, when it went to auction, I had all these publishers trying to sell themselves to me. It was hard to take all that in, especially as someone coming from Southall. You’re nobody in Southall! It’s a small migrant town, nothing happens to people in Southall. I liken it to working class footballers who get taken on by a big club. Suddenly, they’re being paid money and attention, and that’s how it felt to me. I don’t want to say it was too much, because that makes it sound like I’m being ungrateful, but it was a very big shift to make. I work in a community setting, I work with small charities, I work with people who are socially excluded because I see myself as someone who is socially excluded. And suddenly I found myself in a big publishing house.

What was it like growing up in Southall in the sixties and seventies?

It’s hard to compare it to anywhere else because a lot of people in Southall didn’t go anywhere else. With my family, we were the people who were maybe less adventurous, because we’d come out of the airport and gone to the nearest town, then didn’t go much further. So there was something closed off and insular about it. But that insularity was also quite intensive. I found it exciting and boring at the same time. Beneath the everyday you could probe with a magnifying glass, you could really look at people. For such a small town, there was a lot going on, in terms of music, fabrics, incense burning. It was very stimulating. Very poor, very run down. There were slums in the area, before the Havelock Estate was built, where I grew up. But there was a sense of vibrancy and community. Real, in-your-face poverty, but in some ways that pulls people together. I think Southall is the stimulus for most of my creative writing, it comes from stuff I saw. The wastelands, the cemetery, the temples, the mosques, it’s an artist’s dream. Everyone would have two, three, four, five, six jobs. You’d see the smoke pouring out of the factories. There was a sense that it was the engine of the country, in a way. Migrants working nonstop to keep the country going.

How important were dub reggae and underground clubs like The Crypt to you?

It was like our temple to commune together. Because the Black community, much like the Asian community, wasn’t welcomed into mainstream spaces, so we had to create our own. It was the politics of invisibility, migrants weren’t seen or welcomed. We went underground so as not to be seen or heard, otherwise the police knew where we were dancing and would raid it. But we also went underground because they were the cheapest places: cellars, church crypts. They gave us refuge. They let us hire these spaces for very little money to have our dances. And actually, I thought Southall’s crypt was the only one, but now people keep coming up to me and saying, ‘I didn’t know you used to rave in crypts, too!’ So the Black community was obviously doing this across the country. Dub reggae was the sound of revolution, it was a way of weaponising music to fight against racism and oppression that migrant communities were facing. It was a way of communicating and sounding out how we were feeling, a call to fight back. It was important for that reason. But also it was just pure joy, letting go at the end of the day, to dance and have freedom of movement.

It must be interesting now to see how the music culture that you took part in as a teenager has trickled down the generations in London.

It’s everywhere now! Young people are speaking the language we were speaking back then, it’s taken that amount of time to trickle through. When I hear young people speaking on the bus, I’m like, hold on, we were speaking like that all the way back then! All those words you think are cool and new, they’re not new. The tracksuits, the bling, the gold, that’s come from us, too. Fashion was thriving back then. Hiphop has come from dub reggae. A lot of punk musicians experimented with the mixing board approach of dub reggae. So I think a lot of what people listen to now has come from dub reggae and that particular culture. I pick up on it a lot, in the language and vernacular, style and fashion, in particular.

Between 1979-1981, there were uprisings against racism and police brutality across the UK. In Southall, as you explore in Fire Rush, but also places like Brixton, in south London, and Handsworth, in Birmingham. It’s hard for me to make sense of, because I was born a decade later, but most of my reading of Southall’s history of standing up to racism has been from a Punjabi or South Asian perspective. I enjoyed reading about it from a Black Caribbean perspective.

Everyone was there. The Asian community, the Black community, the Irish community. Everyone was there because everyone felt threatened, tension had been brewing for a long time. There was poverty and police brutality. A young Asian man had been killed. It was almost tangible, in the air. And when we heard that the National Front were going to march through Southall, the whole community came together. Like I show in the book, there were Asian musicians playing next to Black musicians, there were the white punk guys there. The whole community did come out together. But yes I do think about it from a Black Caribbean perspective, because those were the people I was speaking to and with on the day of the riots. If was an explosive time. It was like a dub reggae song: it built up and up and up until something had to give at some point. The community were like, that’s it, we’ve had enough, and there were whisperings about needing to be ready for the National Front: we knew it was going to be tough, we knew the police were going to be after us.

We’re speaking four decades later. How have British race politics changed?

Young people now are different because the policies that were put into place back then have impacted on how they think. That generation are less likely to be racist and are more open. So I think there is change in that direction. You see more mixed relationships, the clubs are mixed, whereas before, in the seventies, the Black club was the Black club, the white club was the white club. So things have changed. But we’ve still got a long way to go. There is still a huge amount of institutional racism in systems like police and education, for example.

There is a strong sense of community in the book, which echoes what you do in your day job, right?

People think I am a writer, but I’m not a career writer. Five days-a-week, six days-a-week, sometimes seven days-a-week, I am working in a community setting. I used to run a charity for children and families, now I support charities and community groups, helping to develop projects for young people, for minoritised elders. The most important thing I do is help to raise funding. I don’t think of myself as an activist, I think of myself as a collaborator. Communities are able to fight for themselves, but what they need are the resources. I help them to access funding to deliver work to young people. It’s all based on my experiences in Southall, where I saw so much talent in young people that was never realised because there weren’t the material resources, there wasn’t the support, there were no youth clubs, no activities. I am driven by how much untapped talent falls by the wayside. It’s voicelessness. I think in my writing, too, what I try to address is the voicelessness of individuals, young people and communities.

In Fire Rush, after the first act in Southall, Yamaye runs away to Bristol and then travels to Jamaica. Why did you choose to move between these three settings?

I wanted to show coming from darkness into light, and rising up. My experience in Southall — not the town itself, but my personal experience of family there — was of being in the dark. Then going to another place, Bristol, to run away, but very quickly getting into more difficult situations because I hadn’t lived in the real world. And then when I was 20 I took myself off to Jamaica and thought, ah, this is it, finally, I feel a connection here. For me, the scenes in Jamaica are about coming into the light, but also rising up, because that has been my own journey. But it was also wanting to show the dark underground and coming upwards, into the light. That was my artistic intention.

The Black womanhood that you explore through Yamaye and other characters is offset by the masculine duality of the men she gets into relationships with: Moose, who is sensitive and stable, and Monassa, who is toxic and dangerous.

I’m exploring Jung’s ideas of the shadow. In a way, they are one and the same character: Monassa is the A-side or the darkside of Moose, and Moose is the A-side or the light side of Monassa, like a dub reggae vinyl. We all have light and dark, and I’m trying to show that through these characters.

Fire Rush reads like a catharsis, a healing. Is that fair?

I write because I need to write, it is very much a therapy. I’ve been writing since I was eight. It is a way to make sense of difficult or emotional experiences that I can’t process in any other way than on paper. I do see writing as cathartic. For me, Fire Rush is all about channelling the rage from my childhood into something, transmogrifying it. You can’t change the past, but you can transform it; use this energy, this rage, from what has happened and put it into a story. That’s why it is called Fire Rush, it’s about fire, which is rage. By finishing this book I think some of that rage — maybe 60% — has gone!

In my mind, writing for catharsis is not just about purging your emotions through your art, it’s about reaching other people who can relate to your art.

When you write, you’re writing alone, but you do want to have a conversation. When the book comes out, you want to hear back from readers. You’re writing, you’re communicating, and you want to have a response. What do people think? What is going on in their lives that means they find resonance with the book?

The paperback comes out in the new year. I found that with the transition from hardback to paperback of my book, Cut Short, it started to find its way into deeper community spaces. It became more accessible to wider society.

I’m looking forward to that. Because I wrote Fire Rush for my community. Well, I didn’t write with an audience in mind, but I did think to myself, I would love my community to read this, and they will only read this if I put some music in it, and use a certain language, and so on. It’s good to know that it will find its way there.

Congratulations at having been shortlisted for the Women’s Prize and the Waterstones Debut Fiction Prize! How does it feel?

It’s a privilege, for me and for the community. Because I feel like Black culture has been so undervalued that going from writing about dub reggae, writing in Jamaican vernacular, to be being shortlisted is a recognition that Black culture is high culture. Middle class white culture is seen as high culture, classical music is high culture, but Black music is often seen as low culture. And I hate those hierarchies. So being shortlisted is a bit of recognition to say: this is high culture.

Fire Rush is published by Jonathan Cape (Penguin).

You can follow Jacqueline Crooks on Twitter and Instagram.

All City aims to archive and inspire social change through storytelling.

I teach a monthly course, Writing for Social Impact, at City, University of London, where I explain how to do this in an accessible, collaborative and uplifting way.

It’s a safe space ran across two mornings for writers of all abilities to learn about how to tell stories and make meaningful change with their pen.

If you are between 18-25 years-old and from an underrepresented background and/or facing financial difficulty, there is one free scholarship space available on every course.

The next available course runs across Friday 15th and Saturday 16th December.

You can find out more and book your place here.