Finding My Ancestral Home

This week I developed two rolls of film from a recent trip to Punjab with my Dad. The most important photo was ruined, but the journey that led me there was worth it

Yesterday I took a trip to my local Snappy Snaps to pick up some photos I got developed. Over the last two years, fed up with the numb saturation of smartphone photography, I’ve made a habit of investing in disposable cameras to document my life. It’s taught me to be more patient and selective; to not worry about looking for moments, or capturing them to share with the world, but to let them occur and be present in their company, clicking only if it feels truly worthwhile. This week was the first time I’ve handled rolls of film holding images from a proper camera. It has taught me valuable lessons.

Earlier this year, I travelled to India with my Dad, Vineet. It was my first time in the country since 2014, when I traversed from the mountainous north to the tropical south across three months, and the fourth time since I was born.

We flew into Amritsar, the spiritual home of Sikhism famed for its hearty food, which sits directly across the border from Lahore, Pakistan, and is a short drive from the town of Batala, where my dadi ji (paternal grandmother), Raj Kumari, was born. While staying in a quiet terracotta haveli outside the city centre, refusing to buy a sim card to avoid distraction, we spent a few days walking, eating, talking and visiting the city’s many sarovars (holy lakes), before working our way across East Punjab via car and train over ten days, stopping in significant places along the way. We finished in Delhi, the capital, where I stayed to write and visit friends after Dad flew home.

Initially, I’d booked the trip as an effort to strengthen my next book proposal, which I’ll be sharing more about soon. But being out there with a stomach full of ghee-smothered food and without a language I was never taught, away from the stresses of my education work and abstractions of my writing in London — outside the comfort zone of my English-speaking world — I realised that its higher purpose was to spend time reconnecting with Dad after years of drift since my parents’ divorce. Research was the vehicle. Creating memories became the destination.

I only properly began to grasp this on day six, when we arrived in the hectic city of Ludhiana. Joined by my friend and collaborative photographer, Tristan Bejawn, we sought to find my great, great-grandfather’s terraced house, where Dad was born, the youngest of four brothers, in 1962.

We didn’t have an address, only a sense of direction. We caught an auto-rickshaw from our hotel to the clock tower in the city centre and entered the infamously dense labyrinth of Chaura Bazaar on foot. Ripped paper kites, colourful remnants of children’s celebrations in the days between the yellow-tinted spring festivals of Lohri and Basant, hung from bare electricity wires and lay strewn across piles of rubbish. Pneumatic drills sounded over the hissing of paronthe frying on tawas (flat pans). T-shirts read ‘RIP Sidhu Moose Wala’ beside speakers blaring the late megastar’s hip hop-infused music. Merchants sold cotton rolls, wedding attire and thick, decorative kambal blankets that reminded me of visiting my grandparents’ richly-scented former home in Southall, west London.

As Hindu Pathans travelling south from Kabul, in present-day Afghanistan, Thapars first settled in this stretch of land to help build a new settlement that would expand to become the largest city in East Punjab. I knew from vague conversations with family members that our ancestral house would be a short walk from the preserved home of Sukhdev Thapar, a revolutionary who, as a key figure in the Indian Independence movement at the time, was hanged with Bhagat Singh and Shivaram Rajguru at Lahore Central Jail in 1931, at the age of 23, for killing a British police officer in revenge for the brutality being enacted on local Punjabis. After knocking on doors, we spoke to Sukhdev’s grand-nephew, Tribhuvan, who encouraged us to believe that we were distant relatives. He pointed us in what turned out to be the right direction. Passing a tiny 250-year-old Hanuman temple, where generations of my ancestors would have knelt to pray, within minutes we stumbled across an alleyway corner that made Dad’s eyes sparkle in fond, intuitive recognition.

At first, the house looked hollowed-out and abandoned, so we stood outside and debated our options. A neighbour encouraged us to return in an hour. When we did, the owner had arrived, a man called Manoj Kumar Jassal, whose family had bought the house from my dada ji (paternal grandfather), Vishva Nath, and his brothers in the 1980s. He invited us inside to what was now a sprawling clothes factory making school uniforms and walked us up the flight of stairs, where my eldest uncle, Kamal tayah, remembers waiting for Dad’s first breath while the midwife assisted my grandmother. Climbing over piles of plastic packaging and rolls of material, we ascended to the open roof top where my uncles and grand-uncles and great grand-uncles would have learned to fly their own kites on the same thick seasonal breeze that I could feel lapping against my face. It made for one of the most extraordinary days of my life.

Luckily, Tristan captured it all on his Contax G1 camera. The next day, as he headed off to Jaipur to shoot a story for National Geographic Traveller, he kindly leant the camera to me to keep, with ten shots left on the current film, and a second roll to use when those were finished. My amateur photography career upped a level.

This time, after breakfast on what would later turn into the rainiest day in Ludhiana for four years, Dad and I took a walk from our hotel to Ghumar Mandi Chowk, where rows and rows of tailors uphold the city’s age-old reputation as a clothing capital of south Asia. With the camera strapped in a small bag around my shoulder, I bought a few Nehru waistcoats and replaced my blue waterproof Columbia jacket with one of them as we left.

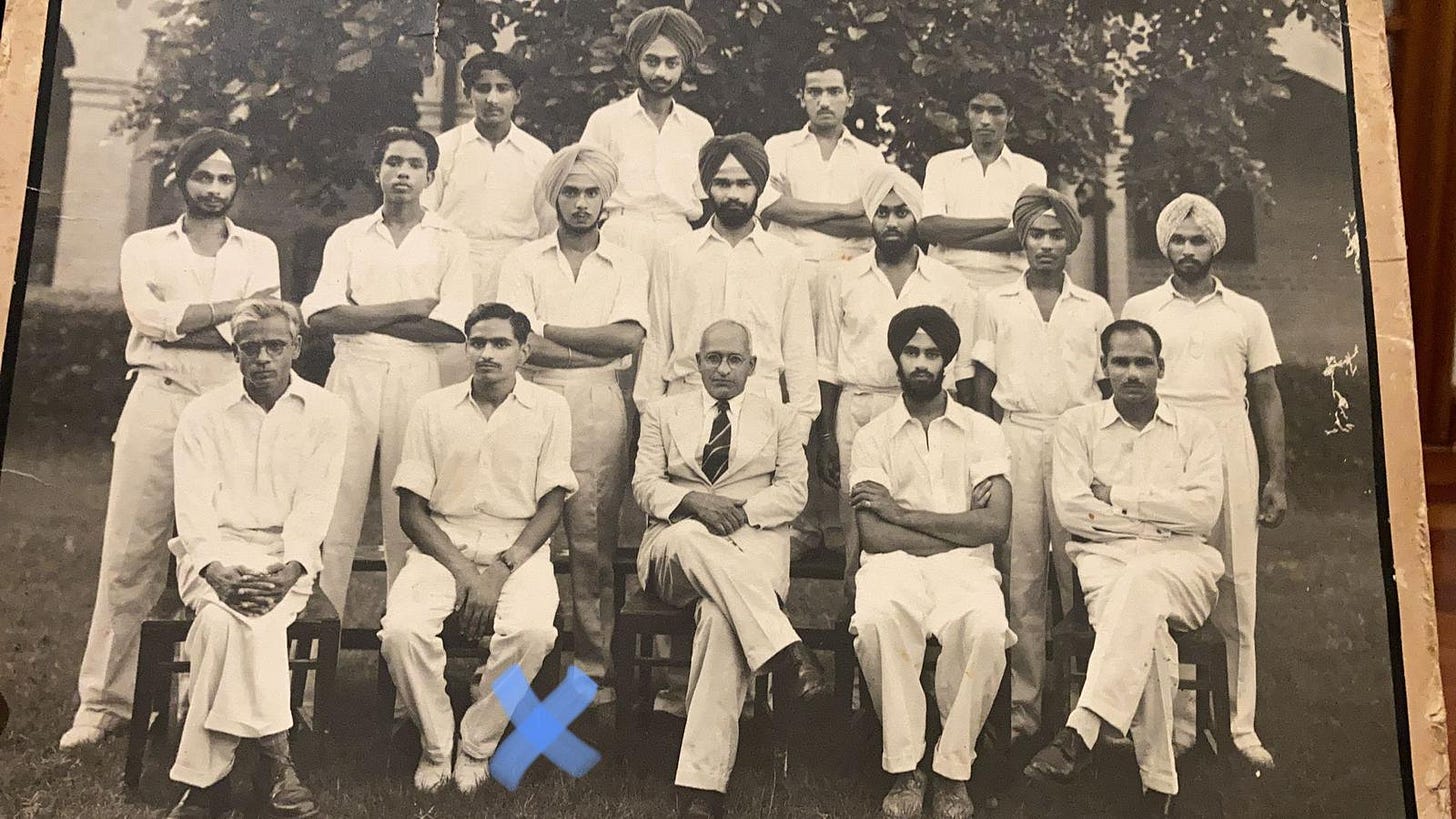

We stopped to eat chole bhature for lunch before heading over to Government College, where my grandfather studied in the years straddling Punjab’s horrific Partition in 1947, when many of his Muslim friends and their families disappeared across the new border forever. He was a few years below the great Urdu writer, poet and musical composer, Sahir Ludhianvi, who would later become his close friend. As parakeets squawked in nearby trees, just like they used to do when I ran up to bowl at my school pitch on the banks of the Thames in south-west London, we completed a lap of the cricket ground where Grandpa had captained the team as a cunning leg-spinner.

I asked Dad to take a seat on the white stands and took what I immediately felt was the most important portrait of the trip — an image that I’d be able to frame and keep forever. We wandered into the middle of the waterlogged pitch that Grandpa would have bowled on, which, boasting a makeshift wicket constructed of grey bricks, has now become neglected with disuse. I handed Dad the camera to take a photo of me in my new waistcoat. The thwack of willow bat on leather ball echoed from behind us as a group of students practiced in the cricket nets.

That night, assuming that it was finished, based on the number dial showing “36”, I went to change the roll of film, not realising it hadn’t automatically rewound already. I popped open the back of the camera and exposed it.

After panicking for a few minutes, as two days’ worth of the most precious memories flashed before my eyes, I figured out how to wind it up manually, replaced it with the second film, popped it in in my bag and tried to forget about it, unsure of how many photos would be affected and not wanting to dwell in speculation.

Which brings me back to this week and yesterday. As I walked out of Snappy Snaps with the paper envelope full of prints, I hurried to thumb through them, arriving at the two taken at the college cricket ground.

Out of over sixty, they were the only two that were completely ruined.

I’ve spent the last 24 hours flitting between disappointment about the results of my amateur mistake and excitement about the other images that came out great.

I’ve settled at the conclusion that — aside from the benefit of learning the most basic lesson of film photography, which I will never, ever forget — I was meant to be there that day with Dad, and Grandpa in spirit. Nothing more.

The whole trip was worth that alone. Little else matters.

By Ciaran Thapar

I teach a monthly course, ‘Writing for Social Impact’, at City, University of London.

The next course is Friday 12th & Saturday 13th May 2023.

A fully-funded place is available for a young adult (18-25 years-old) from an underrepresented background and/or facing financial difficulty.

The ruined photographs are strikingly beautiful, the human figures like ghosts behind the splash of bright red and yellow

I Lmistvdidntvread this, but my attention was caught by the fact that you were looking for evidence of family history, which I have done. Them I googled chole bhature, and realized what binds us together. My grandmother taught me to make bread when I was just a little girj in the 1950s. The hand motions in the video were so similar, it took me back in time.

https://youtu.be/QbyXsYOTJD4

Watch "hotel style balloon shaped chole bhature recipe - with tips & tricks | punjabi chana bhatura recipe" on YouTube

Now I will read the rest of your post☺️