Flow Like River

Over the last few years I’ve been managing an artist called Rippa. This is the story so far

During the lockdowns of 2020, one of my esteemed mentees, Jhemar Jonas, who turns 21 next month, started riding empty train carriages across London at night. He would do this armed with a leather-bound paper journal and ballpoint pen engraved with his initials—gifts bought to celebrate the commissioning of my book, Cut Short. As one of the main heroes of its true story, Jhemar had helped me to write it.

On each adventure he would find a bench in a different part of town—Primrose Hill, Canary Wharf, Barbican, Brockwell Park—then sit down and scribble lyrics under the light of a street lamp, before practising them aloud over instrumentals sourced from YouTube on his smartphone. His nocturnal walks and performances-to-self became a meditative ritual.

That summer we met up to go through the first draft of Cut Short. We took seats at a social distance on a patch of grass near the bandstand in Ruskin Park, Camberwell, in south east London. Before I had time to fire up Google Docs, Jhemar had opened up his journal and requested to show me his favourite song, ‘Flows’. He sang it while birds tweeted in the trees overhead.

“If you’re talking flows, then I flow like river. Talking dreams, then I’m dreaming bigger,” went the chorus.

I couldn’t help but smile. I grew up staring out of a childhood bedroom window overlooking the River Thames. My paternal bloodline runs from Punjab, “land of the five rivers.” I felt his words. So I followed the signs.

“You’re serious about music?” I asked him.

“I’m hella serious!” Jhemar replied.

He’d always called himself ‘Rippa’ when he performed music. He announced that he wanted to keep the name.

“What does it mean?”

“It connotes destruction. But man’s gonna destroy things in a positive way: destroy false perceptions, destroy negativity in this world.”

I first met Jhemar when he was 12 at a homework club in Brixton Hill. I was volunteering as a student mentor with the education charity IntoUniversity while studying for my MSc in Political Theory at the London School of Economics. As the story of Cut Short recounts, meeting Jhemar would inspire me to become a youth worker in schools, youth clubs and prisons.

In our initial meetings across the early months of 2015, Jhemar expressed how he found it difficult to focus in lessons at school. He was bright and determined, popular with students and teachers alike, but he often got in trouble for speaking out-of-turn. He occasionally lost his temper. So he had taken to writing his busy thoughts down in raps at the back of his exercise books. He would show them to me with pride.

To anchor our conversations around critical thinking and language skills, I started printing off sheets of UK hip-hop and grime lyrics for us to listen to, discuss and dissect together. We would go on to fill several exercise books with colour-coded notes, like a diligent student preparing for their English Literature GCSE might do with a poetry anthology.

Fast-forward through Jhemar’s teenage years: our trips to different parts of London and feasts of Punjabi food; songs performed at school or church; debriefs about playground fist fights and romantic relationships; heavy-handed stop-and-searches by police; a life-altering family tragedy; celebratory youth activism events; Tupperware boxes of stew chicken or curry goat cooked for me by his mum, Patricia, a social care nurse; wise, cheeky lectures delivered by his father, Michael Senior, a bus driver.

From the first time we spoke, through thick and thin, music remained the binding glue of our relationship.

Music was the remedy.

So after bidding goodbye at Ruskin Park, we got to work. Using funding I was awarded by Youth Music to support young people with their creative endeavours throughout the pandemic, Jhemar invested in home recording equipment, production software and new headphones. He kept riding trains, finding new peaceful spots, writing more bars and calling me to perform them, sometimes within minutes of their creation. He started adding more adventurous melodies and playful ad-libs to his raps. His confidence grew.

Months beforehand, Jhemar had appeared on Annie Mac’s ‘Changes’ podcast to discuss the trials and tribulations of his adolescence—namely, the determination, resilience and strength he upheld following the tragic murder of his older brother, Michael, in November 2017. After the episode aired, Annie stayed in touch. She called Jhemar while he was on one of his night time walks. He told her about his lyric-writing and newfound aspirations to become an artist.

“I want my music to uplift people,” he would say.

Annie organised for him to attend his first studio session with her husband, the acclaimed music producer and radio DJ, Toddla T. The pair of them immediately hit it off. Every few weeks, Jhemar would travel from his home in Brixton to Toddla’s studio in Ladbroke Grove, a stone’s throw from the Notting Hill Carnival circuit. Over countless sessions spread across eighteen months, the pair shared many jokes and plates of food and recorded demo after demo, alchemising the contents of Jhemar’s notepad with Toddla’s production.

When I knew it was studio day, I would check my phone every so often to find a freshly-pressed song forwarded from Toddla to me on WhatsApp. When we debriefed afterwards, he expressed his long-term commitment to helping Jhemar tell his story, given the refreshing message he was pushing in his lyrics—offering listeners hope, without shying away from the harsh realities of young inner-city lives like his.

They kept experimenting, eventually settling on a stylistic compromise somewhere between afroswing, trap and melodic drill, with a catchy pop sheen. In his daring, semi-improvised delivery and sprinklings of patois and slang, the age-old roots of Jhemar’s proud Jamaican heritage (his father was a sound system MC during his youth in Kingston) shone through alongside Toddla’s veteran mastery of modern bass and electronic music.

To witness the work rate—and Jhemar’s corresponding improvement every time I heard a finished song—was mind-boggling. My transition from mentor to manager became a blessing and a learning curve. Toddla and Annie became Uncle and Auntie to Jhemar, and tag-teaming advisers to me about preparing to navigate the music industry.

Just as the makings of a project started to crystallise, I got talking with Theresa Adebiyi, then Head of Marketing (UK) at Venice Music (now Creative Director at Warner Records), about Cut Short. She’d bought a copy for her mum, a former youth worker. I sent Theresa the music that Jhemar and Toddla had been working on. Alongside her committed team at Venice, she saw the vision and helped bring it to life.

Six tracks would eventually make it onto the debut project, Night Time Walk EP, which was released in December 2022. It is exec produced by Toddla T, with help from Coco and Adrian ‘AMac’ McLeod, and mastered by the dubstep legend, Joker.

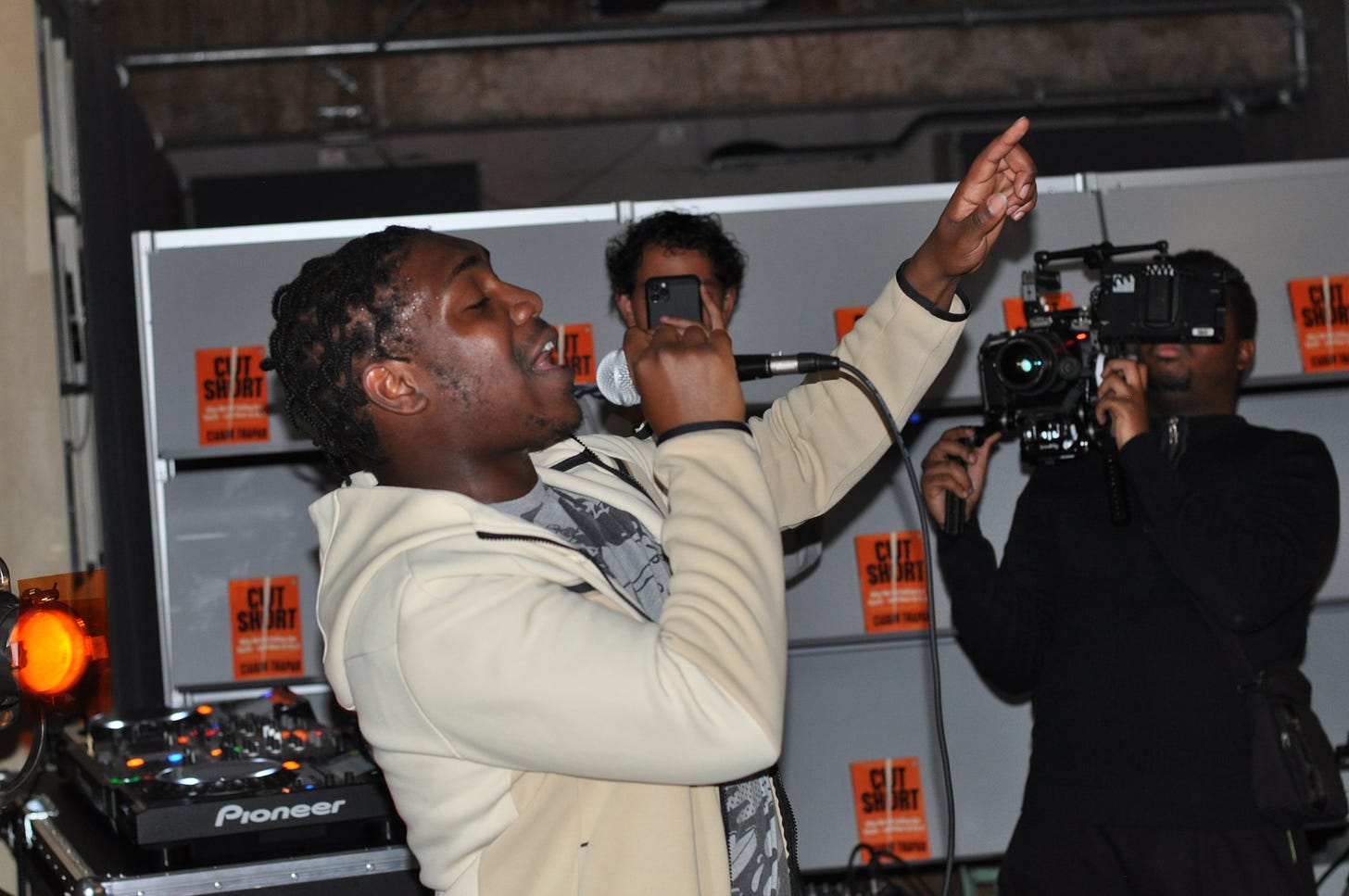

The artwork and videos for the EP’s four singles—‘Flows’, ‘My Bag’, ‘NBAG (Never Been A Gangster)’ and ‘City Lights’—are directed by Ray Fiasco. On release they were added to a wide range of prominent streaming playlists. Rippa performs them whenever he gets the chance, from the paperback launches of Cut Short last summer to the various meetings and summits of people working to end youth violence that he’s attended across the country.

He recently performed ‘Flows’ at the Black Cultural Archives on Windrush Square in Brixton—which feels full circle, as the historic building was the location of our first trip back when Jhemar was 14. The song’s bassline rumbled out of the open window, serenading the street.

Crucially, alongside his unbreakable obsession with music, Jhemar has thrived as a youth worker-in-training in his local community. Throughout any given week he works with young people at-risk of exclusion in schools and PRUs across London, and is often called to train Metropolitan Police officers in effective community engagement.

He recently appeared in a mini-documentary with the online platform, WHY NOW and was interviewed live on Reprezent Radio.

Today, Rob Kazandjian profiled Rippa’s artistic journey for Huck Magazine, which features a joint interview with him and Toddla T.

Watch this space—we’re just getting started.

By Ciaran Thapar

All of my newsletters aim to document or inspire social impact.

If you’re interested in learning more about how to do this, I teach a monthly short course, ‘Writing for Social Impact’, at City, University of London.

It’s delivered over Zoom across two mornings as a safe space for discussion, sharing and feedback.

We cover worked examples, applied moral philosophy, mythic storytelling structure, catharsis and more.

The next course is 17th-18th March 2023.

You can find out more and book your place here.

A fully funded place is available on each course for a young adult (18-25) from an underrepresented background and/or facing financial difficulty. To apply for this, please reply to this newsletter explaining why you'd like to attend.