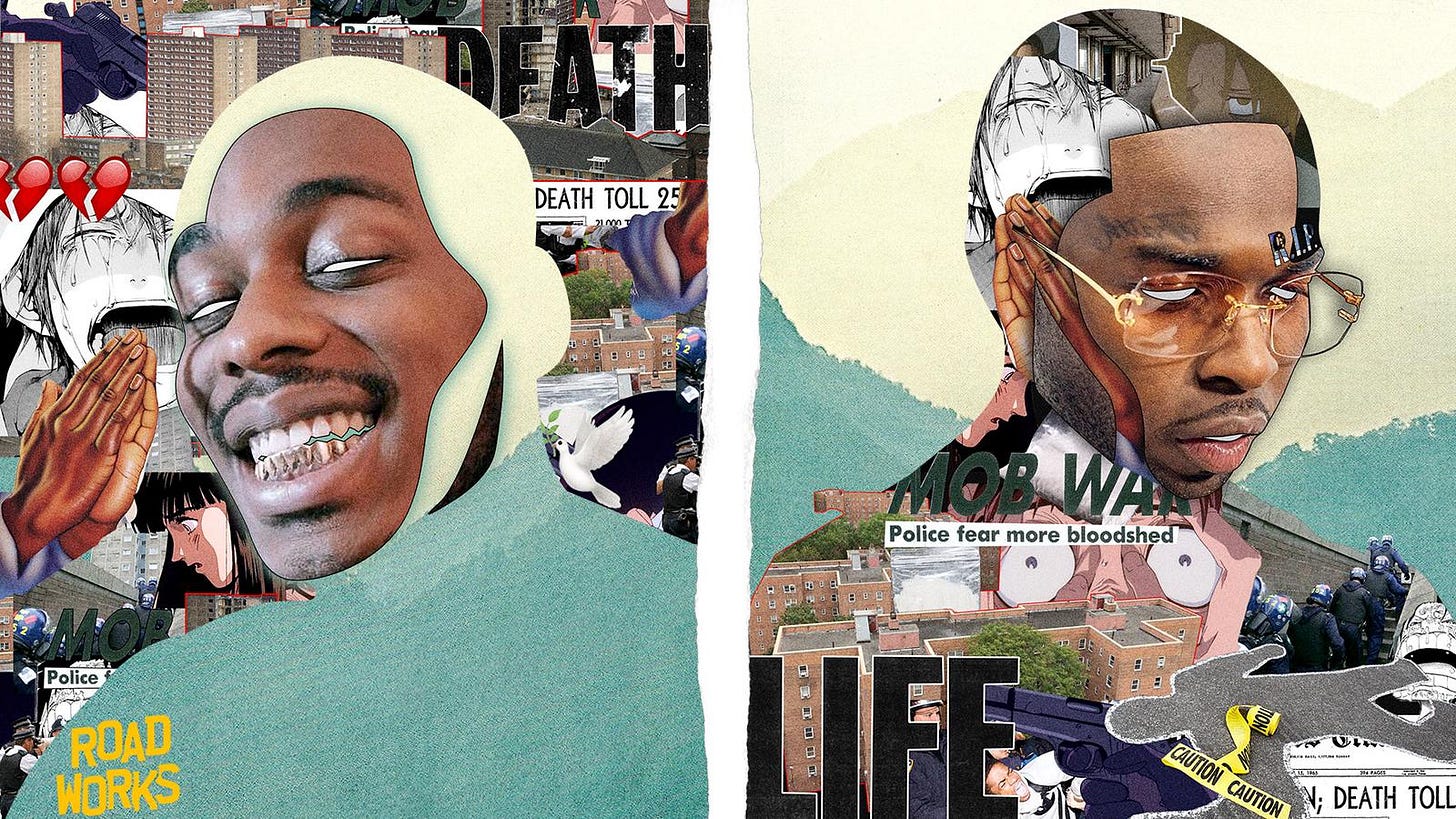

Rap as Catharsis

It’s easy to dismiss violent music as a problem. But understanding that it can be cathartic points towards a solution

Last month I wrote a story outlining my role as an expert witness challenging the prejudicial mining of music content as criminal evidence in British courts. I argued that UK rap and drill lyrics should not be relied upon to convict people, especially without forensic evidence of their alleged crime.

“Each recording can be a purgation of negative emotions,” I explained, hinting at an alternative way of understanding violent songs, beyond simply dismissing them as a problem. In my youth work with teenagers over the last decade—which has included mentoring many rappers with lived experience of serious youth violence—I’ve come to view the narratives of music as a force to be harnessed and critiqued, not suppressed and censored.

To search for solutions, I’ve found it helpful to trace the etymology of a word and idea that’s repeatedly used in common parlance, but rarely interrogated.

Catharsis.

When we describe an experience as ‘cathartic’, what do we mean? Where does it come from? Why does it matter?

In ancient Athens, people would gather at the amphitheatre to watch tragedies play out on the stage. While helping to scribe the origins of Western philosophical thought, in his classic text, Poetics, Aristotle would briefly mention ‘katharsis’ to describe the purgation or purification of emotions felt by performers and audiences of narrative drama.

The specific slant of its definition has been hotly debated for centuries. But broadly speaking, catharsis is shorthand for the belief that stories can serve a moral and social, even medicinal, function. By making us empathetic towards, or scared on behalf of, a fictional character, we confront and drain latent feelings of pity and fear that build up in our lives over time in a controlled setting. By shocking us into new modes of thinking, tragic parables teach us ethical lessons about actions and consequences. Collectively experiencing art brings us all closer together.

Have you ever felt renewed on your journey home from watching a film at the cinema? Perhaps hearing a sad slow jam helped to validate and lift your low mood, an angry protest song motivated you to go harder at the gym, or an excitable banger played at a grime rave made you throw up a gun finger in celebration when the DJ reloaded it. Maybe you’ve read a story about someone overcoming a life challenge, and it made you feel empowered to do the same.

These are examples of catharsis. We experience it all the time.

Philosophy need not remain the intellectual plaything of elite armchair thinkers. There are many ways of applying it to the complexities of 21st century life. Alongside thought experiments like Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and social designs like Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, I’ve discovered a constant, universal resonance in conversations with groups of people when I explore catharsis in my work.

I use it in Pattern, a writing programme for young people at-risk of exclusion from their secondary school that I launched with funding from Nurture UK and the London Violence Reduction Unit. I draw from it while teaching my monthly Writing for Social Impact short course at City, University of London.

Whether it’s horror films, video games or the American gangsta rap that emerged from hip-hop’s golden era in the 1990s, debates about the exaggerated dangers of violent modern art have worn-on for decades. “UK rap and drill music is no different,” I wrote in my piece last month. “But because these subgenres have developed in the influencer-driven social media economy, their lyrics blur the line between reality and virtual reality even more.”

The profiteering aims, promotional algorithms and numb normalisations of hyper-violent content that are now interwoven into so much internet media, including streamed and shared music, do make safeguarding young people online more challenging. Rap and drill music’s inevitably rapid-fire circulation runs the risk of glamorising a criminal lifestyle when it’s funnelled through an aesthetic of marketed glitz.

But catharsis can help us to bottle music’s outpouring of pain and alchemise it into strength. Its logic suggests that when rappers step into the recording studio to perform violent lyrics they’ve written—bloody street observations, wild claims of dominance, hyperbolic threats of bravado—it can be a cloaked but vital opportunity to offload an account of something traumatic that they might have experienced, witnessed or heard about in their community. Recording spoken word over a beat can, and does, provide a lone medium of true expression for marginalised youth, in a harsh world that otherwise affords them little room to breathe. It is essential that we engage with it, while being prepared to critique it, without presumptively denouncing it.

Over the last decade, hundreds of youth clubs have closed across the U.K., spending-per-child in state education has fallen, mental health services have been dismantled and policies to criminalise young people have been rolled-out by a Tory government trying to punish its way out of a violent crime epidemic. In this context of austerity, the padded sound-proofing that wraps around a microphone should be valued as the protective walls of a space in which young people who have experienced violence can communicate with the rest of us.

For some boys and young men I’ve worked with, the studio can, to use the language of Aristotle, facilitate the rare purgation of emotions that have built up from subsistent, conflictive life on the roads. It can allow for a cleansing of shame or regret, a lightening of hidden psychological loads, a chance to be heard.

When the artistic process is complete—when the MC removes their headphones and steps out of the booth—an authentic conversation about the roots of their creation might take place with a trusted adult. Inappropriate or provocative bars can be challenged. A coproduction is forged. In this version of events, a model of youth work that embraces catharsis as a useful tool, music heals and informs.

And that’s just for the performer. What about the listener?

Concern about the young audiences that violent music attracts is understandable. But there is a quick assumption that, because drill lyrics themselves can be horrific in their descriptions and provocations, for example, their impact on the vulnerable young person who hears them must be horrific, too. And there might be some truth to this, particularly for children who are too immature to differentiate between their rights and wrongs, facts and fictions.

But lyrics are mostly just…lyrics. Even if they are based in reality, they are performative, and therefore contain within them the rich seeds of catharsis. Young fans of music are smarter than they’re given credit for. If they’re supported to digest art and culture discerningly, pedagogical gold can be forged.

Time and time again, I’ve achieved breakthroughs with teenagers opening up about their feelings of fear and exclusion after presenting conversational prompts from tragic musical storytelling: lyrics clipped from a song, comparisons made between the styles and abilities of different rappers, screenshots from creative videos.

For those who experience British society as a web of financial insecurity, intergenerational trauma, authoritative tellings-off and insidious microaggressions—in other words, as an inherently violent place—listening to violent music content performs an important function, besides all the hype and excitement. It delivers relatable entertainment and current affairs communication. It teaches raw survival lessons: how to avoid betrayal or trouble; who to trust and not trust; why gang life is, in fact, not all it’s cracked up to be. It opens a unique valve for pent-up emotional release.

In 2023, YouTube and Spotify, even TikTok, is the Greek amphitheatre.

The student who feels scared on their bus journey to and from school because of tit-for-tat territorial feuds. The frustrated teenager who turns up hungry at the youth club while trying to avoid the influence of drug-dealing elders after being sent home early from their Pupil Referral Unit. The excluded, arrested young man who has witnessed more stabbings and shootings than you or I could ever imagine, yet feels judged by their teachers or local police when they act out of turn.

For young people in these circumstances, performing and listening to music can be life-affirming and life-saving.

Marginalisation will keep respawning as our mismanaged country’s cost-of-living crisis and rampant inequality deepens. There are thousands of perspectives for whom hearing the rapped or sung words of an artist spitting their ugly, beautiful truth is therapy.

The evolution of UK rap and drill music is not without its flaws. But it reflects the technologically advanced and relentlessly violent world we live in. It’s worth remembering that these genres are the artistic stories of an otherwise voiceless cohort seeking their own way out of the madness.

Understanding music’s potential as catharsis should be a priority for those of us who care about ridding society of the trauma its lyrics speak on.

By Ciaran Thapar

If you’re interested in learning more about the issues explored in this story, I am co-delivering a ‘Music, Justice and Youth Work’ training with Franklyn Addo and Power The Fight at 10am on Tuesday 21st February 2023.

Book your place here.