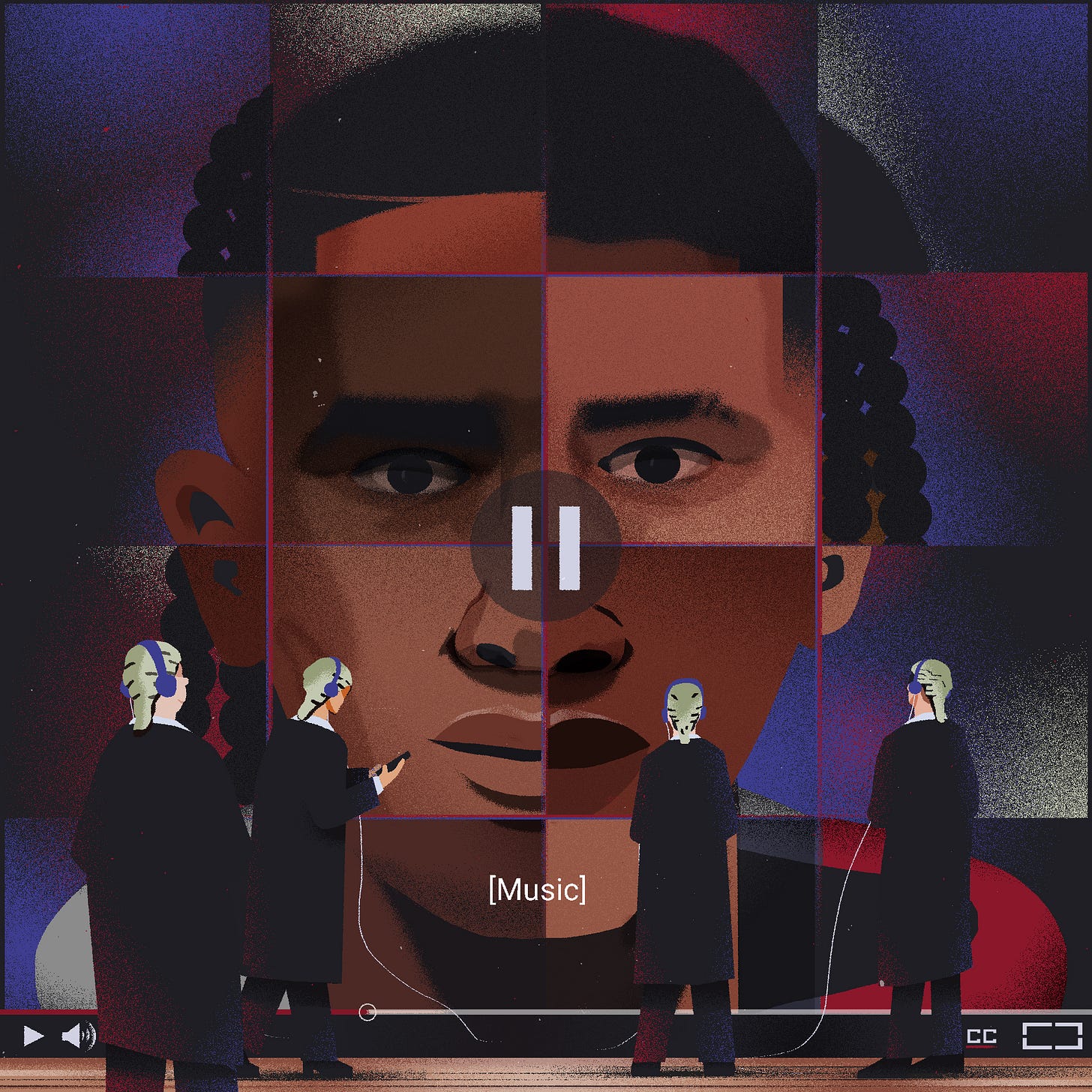

Unsilent Witness (part one)

Social media and online music content is being prejudicially mined for evidence in criminal trials. Over the last two years, I've been challenging it

In February 2021, snow was settling on the rooftops of south London when I received an intriguing email.

COVID was ravaging the world. I’d just finished my book, Cut Short, after six years as an education and youth worker, during which I met hundreds of teenagers in schools, youth clubs, prisons and music studios across London. I’d long balanced frontline work with diary-writing and journalism, and this email would be another step forward on this professional tightrope. It was from a criminal defence solicitor asking me to assist them as an “expert witness”.

Their client, the defendant, was a Black male teenager from south-east London. He was facing charges as part of a group of co-defendants, who the prosecution sought to prove had committed crimes as a gang. The evidence being used was mostly music content pulled from the internet.

A Metropolitan Police officer had written a witness statement in which violent rap lyrics – those of the defendant and others – were misinterpreted as literal, specific and written in the first-person, as opposed to figurative, generic and written as a narrator. The officer had referenced what they believed to be the defendant’s masked appearance in music videos on YouTube. They’d contextualised their conclusions about the defendant’s gang membership with poorly-researched prose about the evolution of drill music – the kind you might expect to read in an A-Level sociology essay, at best.

They claimed, for instance, that UK drill started in 2012, which is impossible, given that Chief Keef had only just kickstarted the genre in its original home of Chicago that year. There were incomplete sentences and spelling mistakes; it was obvious that large chunks of the statements had been copy-and-pasted from previous cases. The word “balaclava” was typed as “baklava”.

The statement presented the act of making music as a criminal endeavour in itself; just a means of glamourising and provoking tit-for-tat violence. It made no concession that a teenager rapping about things they’d endured, witnessed and enacted might be fictional or performative, or serve a therapeutic function, or seek to entertain a mass audience. There was no acknowledgement that getting hundreds of thousands of YouTube views might have required creativity, focus and business strategy.

Finally, the officer had self-identified as an expert on gangs – which they implied covered music knowledge, too – based on the fact they’d spent years policing the part of London in which the alleged crimes took place and where the co-defendants had grown up. Is it possible to be an objective expert about groups of young people if you only interact with them in stop-and-searches? Your guess is as good as mine.

I was tasked with providing my own history and interpretation of UK drill music; commenting on whether making the music or appearing in its videos equated to gang membership, and giving my opinion on whether the officers had demonstrated sufficient expertise about local music culture and gangs.

I spent days poring over the case files and writing my response. Following its submission, the evidence was withdrawn by the prosecution, meaning that it would not feature in the trial. The young man would be tried as a person, not an assumed gang member. His music would not send him to prison – not this time, anyway.

Since then I’ve been called upon many times as an expert witness. The job involves writing a statement about the evidence of an upcoming trial where relevant expertise falls outside the knowledge of a judge or jury. Cut Short, which took me three years to write, at 356 pages long, amounts to roughly 110,000 words. Cumulatively, I’ve now submitted not far off this in witness statements.

The role has remained mostly remote. I end up shouldering a strange, sometimes overwhelming moral responsibility. The partial weight of a young person’s freedom can be dropped or carried in the precision of my words. The bizarreness of this isn’t lost on me – it keeps me up at night.

Many cases I’ve worked on, due to there being a lack of forensic evidence, hinge entirely around lyrics. They arrive in my inbox typed-up and formatted in colour-coded, dense tables. Observational lyrics are commonly mistranslated into admissions of guilt by the police officers analysing them. Sometimes they are lyrics that defendants have written in their iPhone notes app – even when they’ve not been performed yet. Sometimes they are lyrics that were recorded many years ago, despite the alleged crime taking place much more recently.

Screenshots of music videos are accompanied by speculative and overly literal interpretations about their content. If two artists happen to be wearing the same colour t-shirt or tracksuit, could it be their “gang colour”? If someone signals a letter of the alphabet with their hands, or raises a gun-finger, is it a “gang sign”? The police will speculate that it might be.

These are just a few examples – and that’s just music. Instagram pages, YouTube comments and Reddit threads gossiping over gang rivalries are screenshotted. UrbanDictionary is deployed to interpret the meaning of slang. Known family connections and phone contacts are highlighted, meaning that simply having grown up within a tight-knit inner-city community becomes an incriminating characteristic, rather than an unavoidable fact-of-life.

These police statements, referred to as “gangs evidence”, are often submitted right before trial, so that defence teams have limited time to instruct someone like me – their own witness – to respond to it. I am routinely asked to turn my own statement around in a matter of days.

Prosecutors habitually present co-defendants as gang members – grouping them together as one to secure a larger number of convictions. “Gang” itself is used as a word and concept repeatedly, fluidly, and, if it isn’t challenged, to lean on stereotypes and construct racial profiles about the defendants before trials even start. Most cases I’ve worked on have involved Black and mixed-heritage young men. Many of them have been teenagers.

What is real and not real? What counts as truthful expression, and what counts as posturing? Can art be both? Leveraging technology to solve crimes makes sense, in theory. But in practice, taken to a logical extreme, we’ll end up trying to solve “pre-crimes” like Tom Cruise in Minority Report.

I’ve found rare, tribal solace when I confer with other witnesses, like fellow members of Prosecuting Rap, a research project based at the University of Manchester, to which several academics and other writers contribute. If our statements lead to evidence being withdrawn, we are not required to attend court. If we are invited to be cross-examined – which I’ve experienced once – we are expected to stand up in court and answer questions asked by the defence and prosecution about our claims.

It is in these moments – waiting in high-ceiling rooms, surrounded by oak panelling and people wearing barrister wigs; having court days pushed back weeks and then months – that you realise the full extent of the madness. Most older adults are still coming to terms with the mere existence of social media, let alone the mind-boggling speed of TikTok, the nuances of British rap or the respawning etymologies of slang.

But these are the people overseeing the metaphorical guillotine that now hovers over a whole generation of lost youth. Young people who have grown up under a mounting cost-of-living crisis, cared for by public services — youth clubs, schools, the NHS, the judiciary itself – that have been gutted by austerity.

My account here isn’t an excuse for the acts of violent criminals. It isn’t a justification for barbaric digital or musical content. But there must be other ways to move forward. I’ve spent the best part of a decade investing my time, thought and ink into preventing violence, and supporting young people to navigate our complex, hostile world critically and safely. Locking everyone up fixes very little. If nothing else, let this be a reminder: be careful what you write in your lyric book.

By Ciaran Thapar

If you’re interested in learning more about the issues explored in this story, I am co-delivering a ‘Music, Justice and Youth Work’ training with Franklyn Addo and Power The Fight on 21st February 2023.

Book your place here.