Teaching Lyrics and Literacy in Youth Prisons

This summer I delivered writing programmes at Oakhill STC and Feltham YOI, using UK rap and drill music as a syllabus. Art by Raj Dhunna

Towards the end of the summer just gone I was sat in a corner of the ‘corner room’ on Curlew Unit, a wing on the A Side of Feltham Young Offenders’ Institution (YOI), peering out the barred window onto a groundsman steering a lawnmower. Green blades of grass flew chaotically into the air behind him.

As I used to do from the wooden desk in my teenage bedroom at my former family home in Staines-Upon-Thames, only a few kilometres up the road, I watched a blue sky dotted with low-flying aeroplanes taking off from nearby Heathrow airport. A Michael Jordan poster pinned to the wall above me framed a quotation about facing failure to achieve success. Notes from a workshop I’d ran the previous week — random words like ‘teeth’, ‘respect’ and ‘bully’, remnants of a creative writing exercise — were still scribbled on the white board.

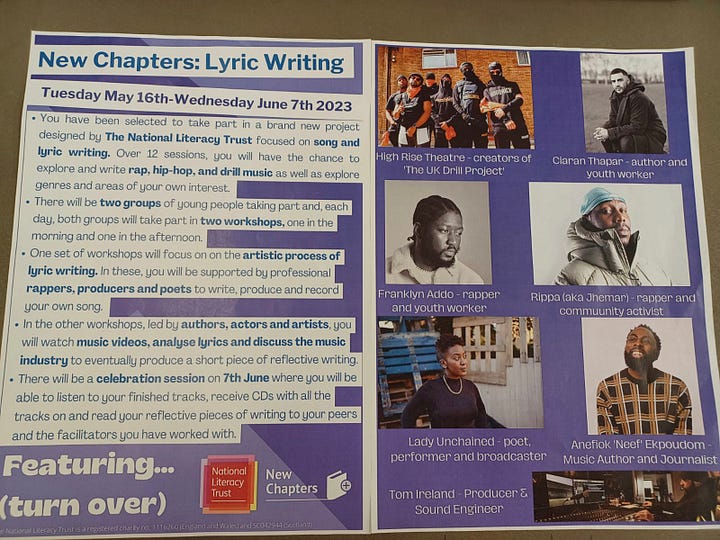

It was the final day of the New Chapters lyric-writing programme at Feltham, which I co-led with the National Literacy Trust. Over four days, split across two weeks, groups of young men aged 15-18 took part in discussion, writing and music workshops that would conclude with the recording of a podcast and mixtape of their songs.

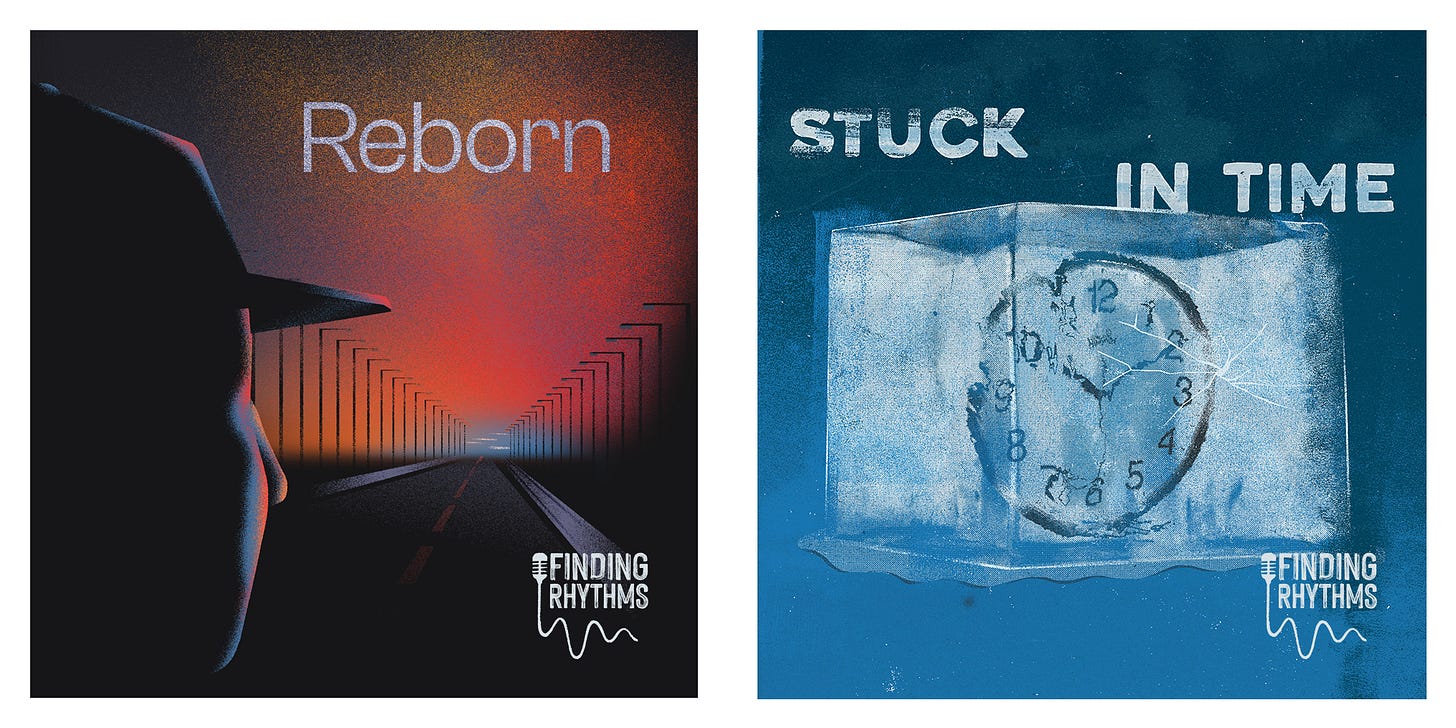

The programme was a collaboration with Finding Rhythms, a charity which delivers music-making courses with people at-risk of offending. Over recent years the organisation has worked with over 750 participants in 36 prisons, as well as in probation and community settings, across the UK.

I led a series of discussions about music in the media, the censorship of UK drill and the role of music in society with help from youth worker Demetri Addison. In the room up the corridor, lyric-writing and recording sessions were led by poet and National Prison Radio presenter Lady Unchained, rapper, activist and writer Franklyn Addo and producer-MC Tom Ireland aka Tom In The Chamber.

We were in the corner room holding the final session on Curlew Unit as a last-minute improvisation. Things were not going as planned — not that they ever do. As is standard across the summer months, due to seasonal overcrowding (with heat comes more youth crime) and understaffing (staff take holidays), education had been cancelled for the afternoon.

So we’d decided to walk from the education building over to the wing where the young people were being held. We asked the prison officers there if we could use the cramped corner room as a makeshift classroom. That way, the final chunk of our trip wouldn’t be wasted, and the young men could complete the full journey of the programme whilst enjoying the promised and hotly anticipated chance to record their own music.

Each of the boys took their turn recording verses that they’d prepared in their notebooks on the portable studio equipment that Tom had carried over in a wheeled suitcase. The clock was ticking before they would be locked up in their cells for the day and we would need to leave, so they had to lay down their lyrics quickly, in only one or two attempts.

Concessions of guilt about missing loved ones, reflections on grief, poverty and injustice, and hopeful, determined affirmations and plans for the future poured onto the microphone, sealing the programme shut. As we shook hands to say goodbye at the end, one of the participants mentioned that he’d already read the Prologue of my book, Cut Short — signed copies of which had been handed out to everyone in the morning — and found it relatable as a south Londoner.

It was a powerful moment of closure that memorialised the hours of rich conversations and debates that we’d had over the previous days. When we left for the day, Franklyn and I went on a drive and walk through Richmond Park as the summer sun beat down to clear our heads and debrief the intensity of the work. We were tired but grateful — as it is tempting to feel after exiting a prison — to enjoy such freedoms that can so easily taken for granted, in normality.

Earlier in the summer, I delivered the same programme at Oakhill Secure Training Centre in Milton Keynes, the only prison in the country which looks after children as young as 12. In classrooms, stools are screwed into the floor. Teaching there means competing with the distractions of constant fights, bangs and yells in the corridor outside. But workshop by workshop we got through it, and got to know two further groups of boys in the process, who would be locked in a room with us for two hours at a time.

To deliver my side of the programme, in one workshop I was joined by author Aniefiok Ekpoudom, who read an extract of his forthcoming nonfiction book, Where We Come From: Rap, Home and Hope in Modern Britain, and used songs like Frontline by Pa Salieu, Streatham by Dave, and When I Was Little by Potter Payper to inform writing exercises about home and belonging. On another day, Fahad Shaft from HighRise Theatre ran a workshop about musical theatre, using clips of the company’s award-winning production, The UK Drill Project, to spark debates about challenging audiences’ perceptions through performance art.

In one exercise, I played the boys Energy by Digga D and asked them to write a paragraph about how they protect their own energy. In weeks to come I would show Digga some of their answers when I interviewed him for the Guardian, and it inspired him to open up about his responsibility as an artist, all of which I included in the finished profile.

Meanwhile, in another room, the same two groups attended a series of lyric-writing sessions, again with the likes of Lady Unchained and Franklyn, as well as Jhemar Jonas aka Rippa, before recording tracks, with Tom again on production. The combination of providing a safe but flexible space to take part in critical conversations about music before giving them a platform to step onto the mic meant the participants were able to uncover and order their thoughts, gain inspiration from other artists, and be guided to make sure their lyrics were appropriate – honest but safe, truthful but smart, raw but listenable.

To close the programme, their writing and songs were shared at a celebration event, where staff listened to the music they’d recorded: it included letters to mums, nostalgia about home, and cheeky musings on romantic desire, as well as commentaries about street life and manifesting positive change.

The two mixtapes of songs from Oakhill were printed onto CDs and sent to their creators to keep and listen back to. I’m pleased to share that both are also available to listen to on Finding Rhythms’ Spotify profile, with cover artwork by Raj Dhunna.

Amazing work, Ciaran. Good vibes your way.

You are so cool I love when you drop a new All City